In recent weeks, concerns over bank solvency have resurfaced in the markets, with Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) being taken over by regulators and UBS acquiring Credit Suisse for $3.2 billion. The takeover of SVB marks the second-largest bank failure in U.S. history and the most significant since the 2008 financial crisis.

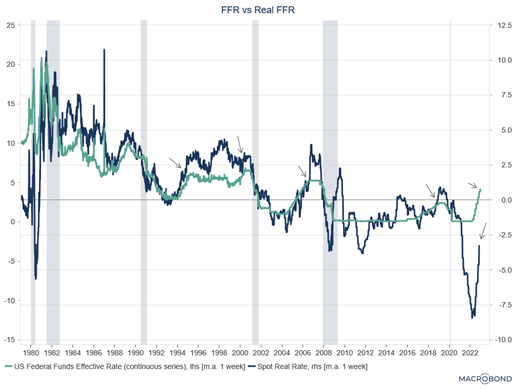

Why it matters: While some attribute the recent events to executive mismanagement, we contend that they are symptomatic of a broader systemic issue. Rather than isolated incidents, they may represent the opening act of a potential future collateral crisis. What’s particularly worrisome is that if the collateral in question is so-called “risk-free” government bonds, we could be entering uncharted territory, leaving us with little recourse to address the issue. The short-term impact of recent events could be a significant curbing of credit to the economy, while the long-term impacts could pose an even more significant challenge to the financial system than the Great Financial Crisis.

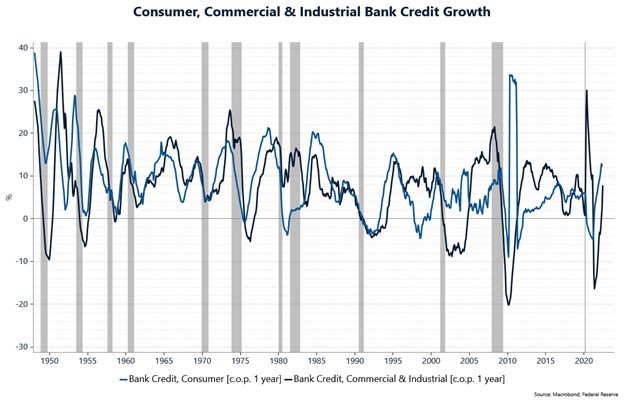

The short-term effects of the most recent banking stress will be to reduce credit in the economy.

- Regional banks are likely to curb credit for three primary reasons:

- First, increasing regulation and the risk of executive prosecutions for mismanagement will create a risk-averse environment, leading these banks to reduce lending.

- Second, the newly formed mechanism that gives these banks direct access to the Fed will increase the relative attractiveness of securities that can be posted as collateral, thereby decreasing the attractiveness of loans.

- Lastly, the drop in deposits in these banks will create a hole that must be filled through wholesale funding provided by money market funds. While access to funding won’t be a problem, the rates charged for this funding will be higher than those on deposits, increasing costs for these banks, thereby pressuring their margins, reducing their profits, and potentially disincentivizing them from making new loans.

- The recent events will also impact large banks, causing them to take a risk-averse stance for two main reasons.

- First, the FDIC is not backed by taxpayer money but by the banks, particularly the well-run large banks. Apart from the direct cost of insuring all deposits of SVB, the possibility of new regulations requiring the FDIC to insure a larger portion of deposits will drive the profitability of these banks lower, reducing their willingness to lend.

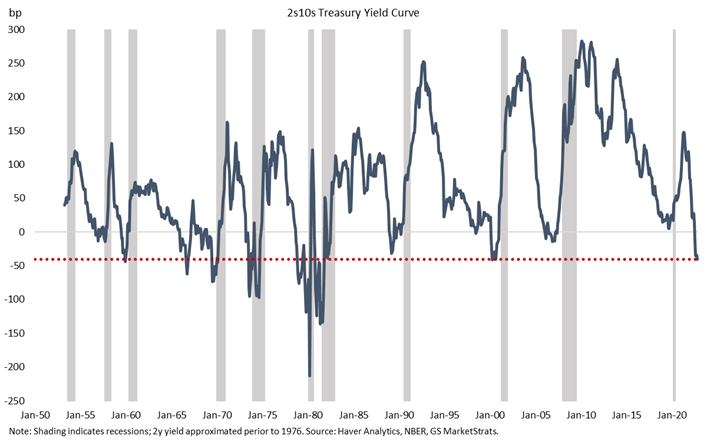

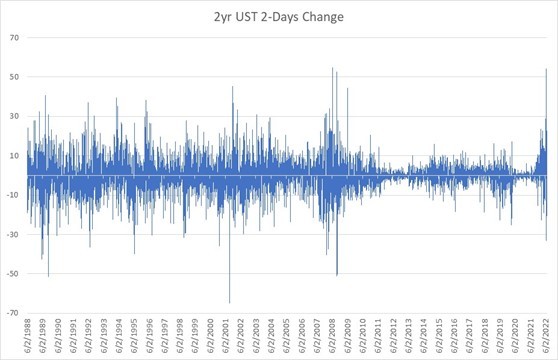

- Second, with regional banks now having direct access to the Fed, there is a new price-insensitive buyer of Treasuries that could pressure long-term rates lower while the Fed keeps the short-end of the curve higher through its hiking cycle, making curves flatter and reducing bank profits and their willingness to lend. These factors could lead to tightening credit and financial conditions, which could have significant implications for economic growth and stability.

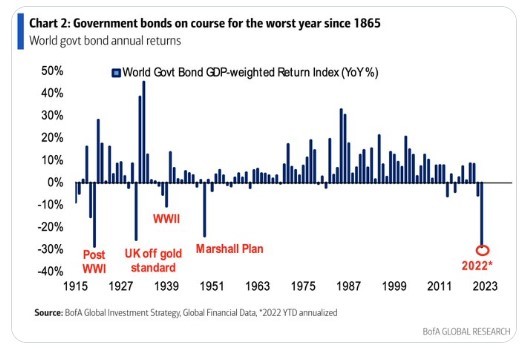

The long-term effects of the debasement of US Treasuries could be catastrophic to the global financial system.

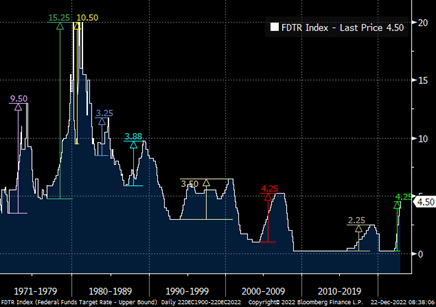

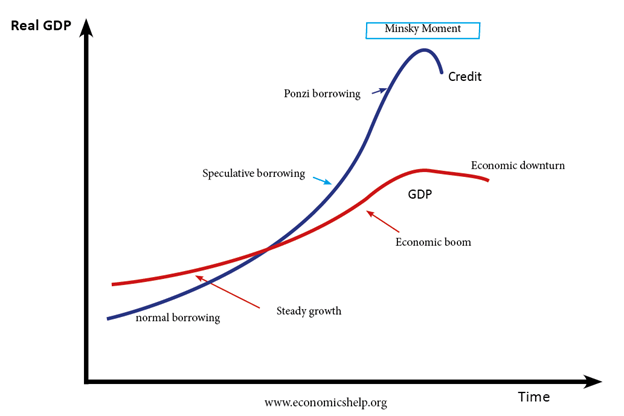

- While it’s true that critics have pointed to mismanagement as a contributing factor in the sudden collapse of SVB, this only scratches the surface of a more significant issue at play. Banks were led to invest heavily in risk-free (US Treasuries) and quasi-risk-free (government-guaranteed) assets due to financial repression and regulation. “Hold to maturity” accounts further fuelled this trend by increasing the allure of such assets, leading to a dangerous level of complacency among banks. Therefore, while SVB may have been the first to fall, the underlying problem is much more pervasive and requires a more comprehensive solution. The possibility cannot be dismissed that we may be witnessing the initial signs of what could be the most significant Minsky Moment in history.

Named after economist Hyman Minsky, a “Minsky Moment” refers to a sudden collapse of asset prices following a long period of growth. Minsky believed that during periods of economic stability and growth, investors and lenders become increasingly complacent and take on more and more risk. This leads to a build-up of financial fragility, with borrowers becoming increasingly over-leveraged and lenders becoming more lax in their lending standards.

Eventually, the economy reaches a tipping point where borrowers can no longer meet their obligations, and the value of assets used as collateral declines rapidly. This triggers a panic among lenders and investors, who try to liquidate their assets, causing a further reduction in asset prices and triggering a financial crisis.

Minsky moments have been observed in many historical financial crises, such as the 2008 global financial crisis, the dot-com bubble burst in the early 2000s, and the savings and loan crisis in the 1980s.

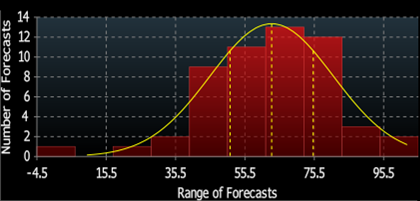

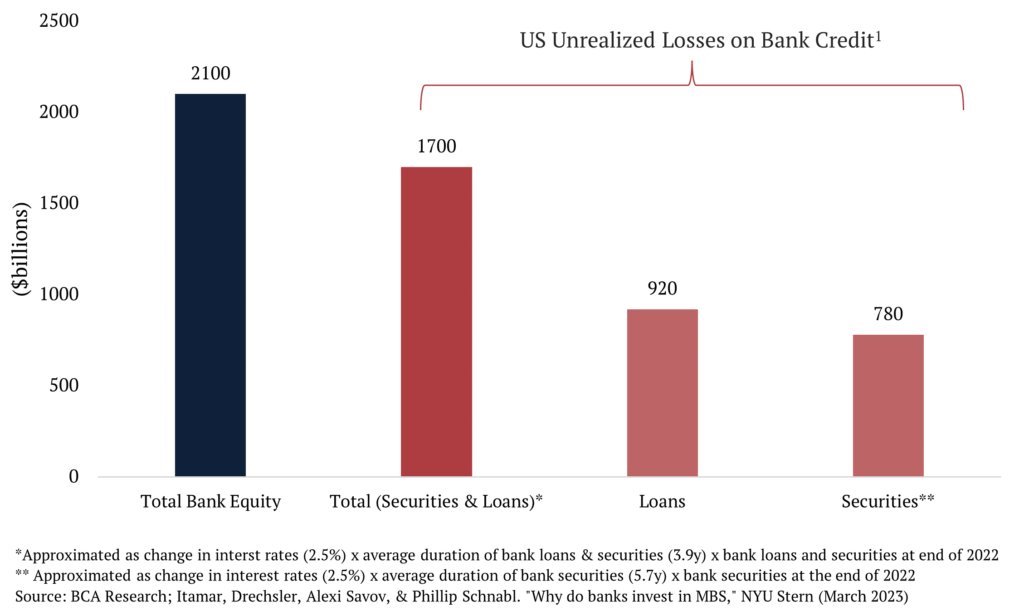

- It’s worth noting that the estimated losses on securities only represent a fraction of the total unrealized losses that banks have experienced due to the rise in interest rates. Loans, much like securities, also experience a decrease in value when interest rates increase. With a total of $17.5 trillion in loans and securities as of December 2022 and an average duration of 3.9 years, the total unrealized losses on bank credit amounted to approximately $1.7 trillion (calculated as $17.5 trillion x 3.9 x 2.5%). This figure is only slightly less than the total bank equity capital of $2.1 trillion in 2022, indicating that the losses resulting from the interest rate increase are on par with the entire equity of the banking system.[1]

- While it’s crucial to consider losses incurred on assets, even if they are unrealized, the most significant issue is the impact those losses have on a bank’s ability to refinance its outstanding debt. Financial institutions rely heavily on short-term, wholesale dollar funding through collateral considered “safe.” However, a lack of such “safe” collateral can lead to a catastrophic failure of the financial system. Therefore, while the losses on assets are important, the loss of confidence in the ability to refinance their outstanding debt poses the most significant risk to the banking system.

A prime example of the risks associated with a lack of “safe” collateral can be seen in the lead-up to the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. JP Morgan provided cash to Lehman Brothers to conduct its daily business. However, as Lehman’s collapse loomed, JP Morgan began to question the value of the collateral that Lehman had pledged, suspecting that it was worth less than initially claimed. As a result, JP Morgan required Lehman to pledge more collateral as a condition for continuing its operations. This scramble for the most “pristine” collateral highlights the dangers of a shortage of “safe” collateral, which can ultimately lead to a decrease in USD funding worldwide as chains of wholesale dollar transactions begin to unravel.[2]

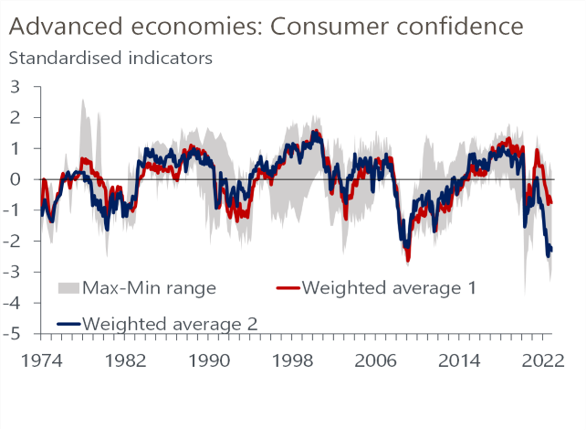

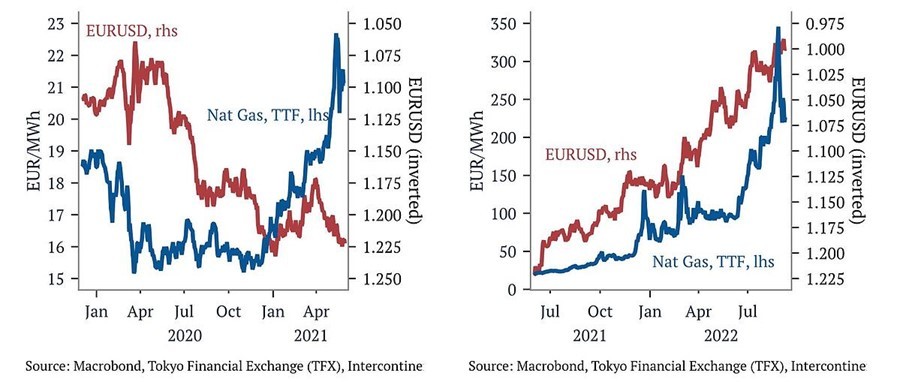

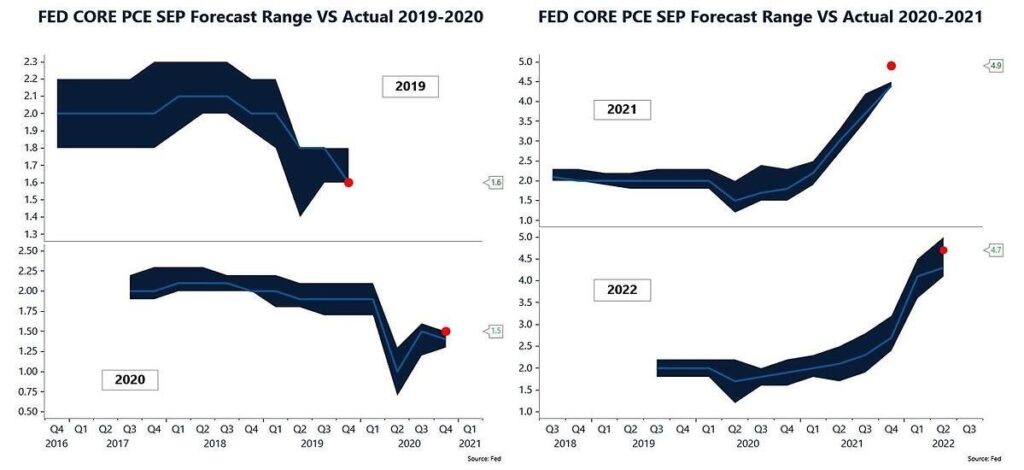

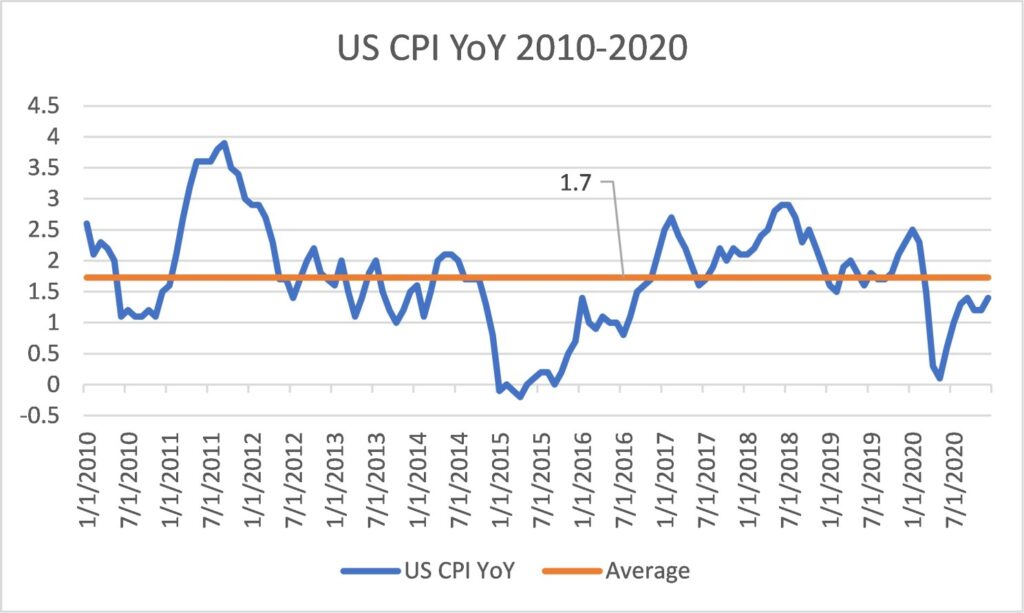

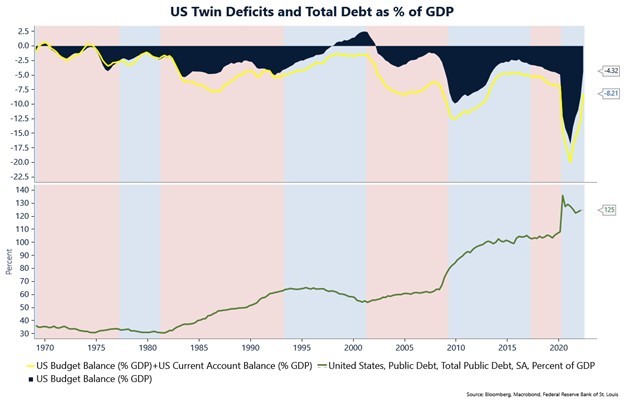

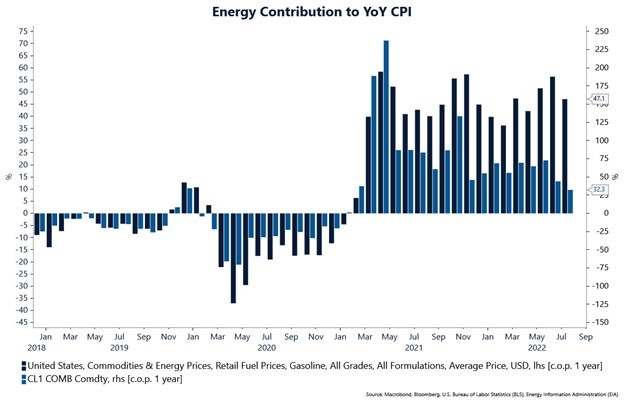

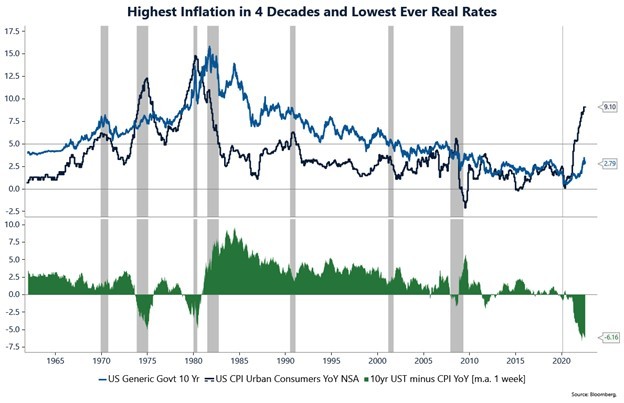

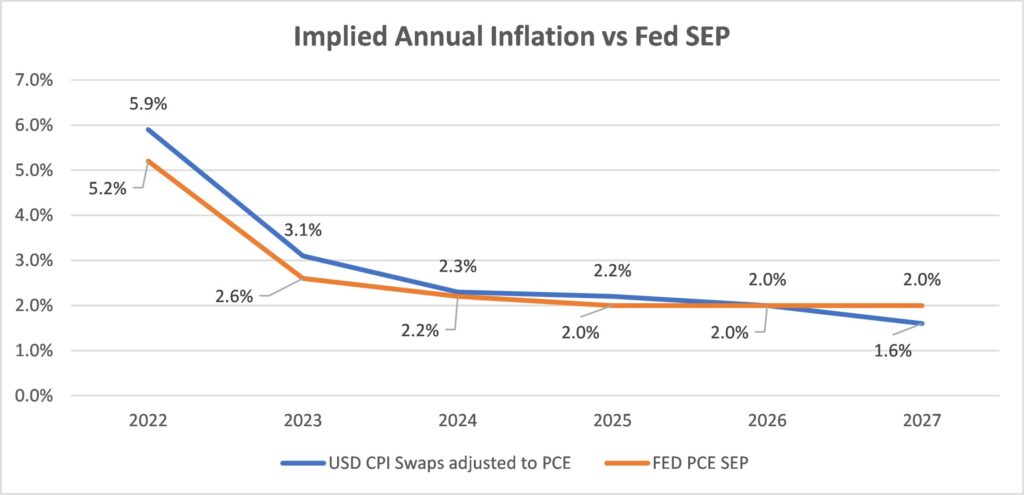

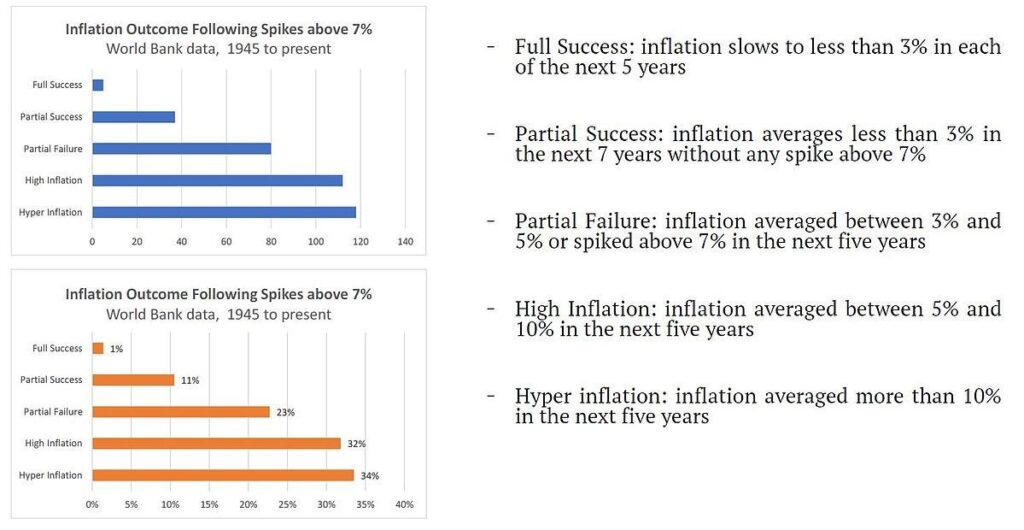

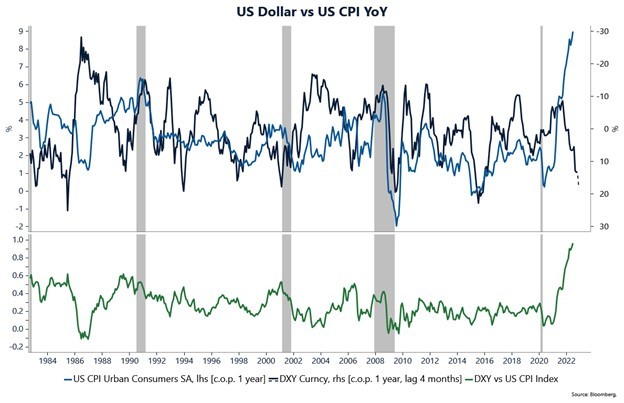

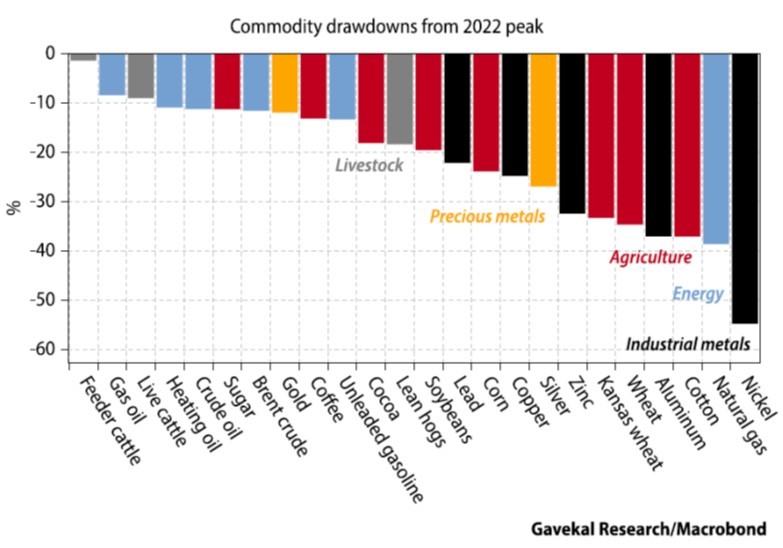

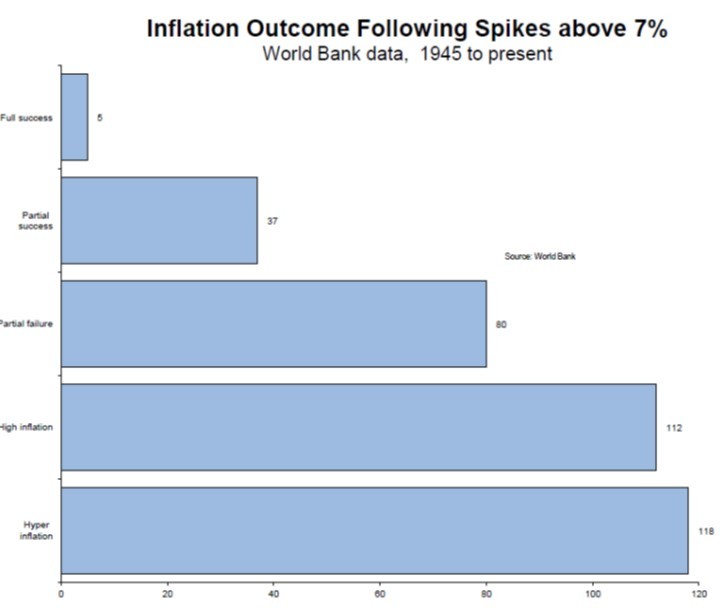

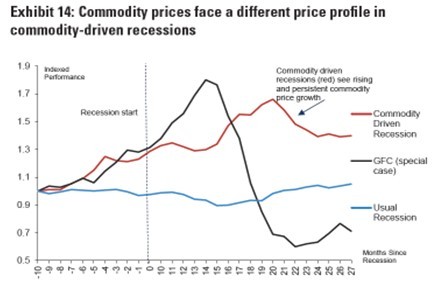

- What could cause the debt of a sovereign country with a free-floating exchange rate and holds reserve currency status to become risky? Inflation. The Fiscal Theory of the Price Level suggests that higher inflation may be forthcoming, which could lead to the “risk-free” status of government bonds being called into question. If this were to occur, it could potentially leave us in uncharted territory with few tools at our disposal to address the issue. Therefore, inflation poses a significant risk to the perceived safety of government bonds and could have far-reaching consequences for the broader financial system.

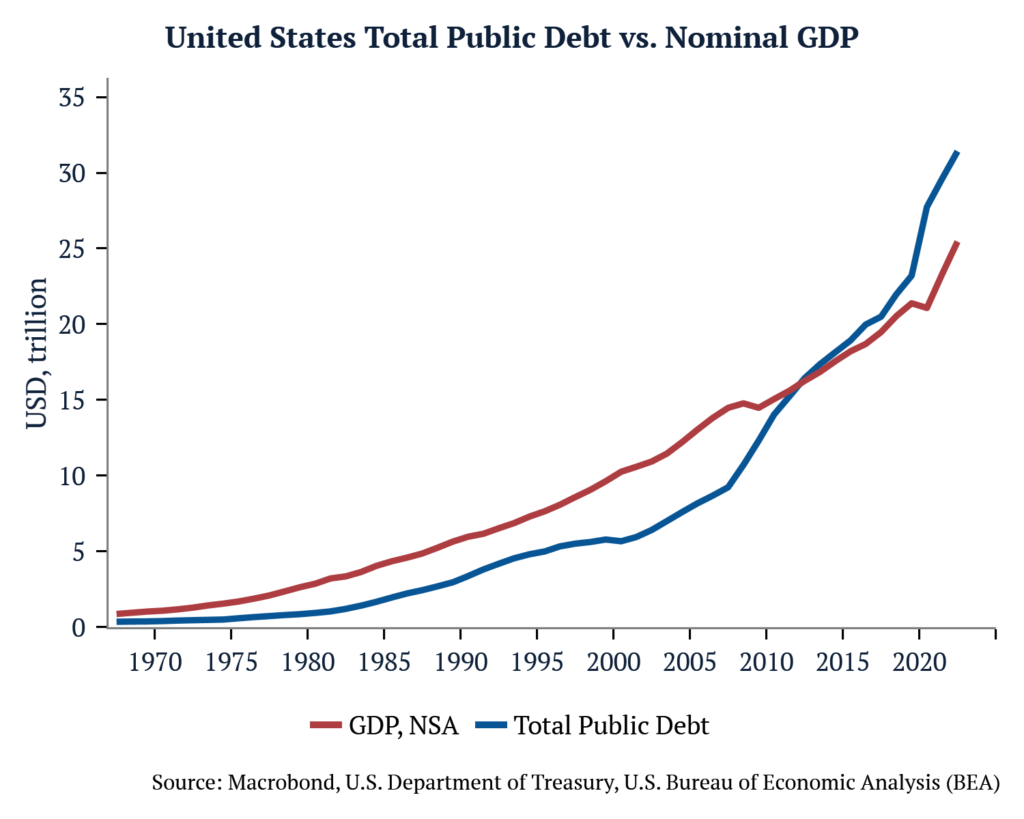

The majority of U.S. government debt is issued with a nominal face value in U.S. dollars, meaning its real value or purchasing power is determined by dividing the value of outstanding nominal debt by the price level. The intertemporal government budget constraint stipulates that the real value of debt is linked to the real value of future surpluses. When considering the intertemporal government budget constraint as an equality, changes on the right-hand side (such as increases or decreases in future fiscal variables) correspond to changes on the left-hand side (i.e., real debt). Since the nominal value of outstanding debt is predetermined, the price level is the variable that adjusts to reflect changes in fiscal variables on the right-hand side of the constraint.[3]

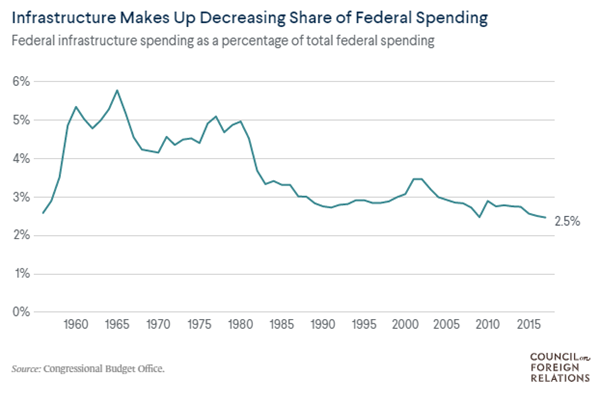

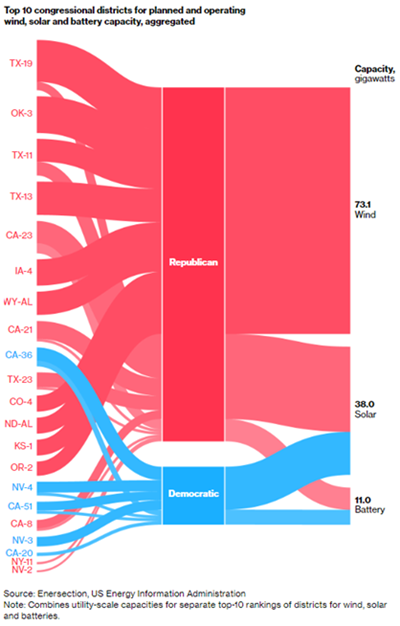

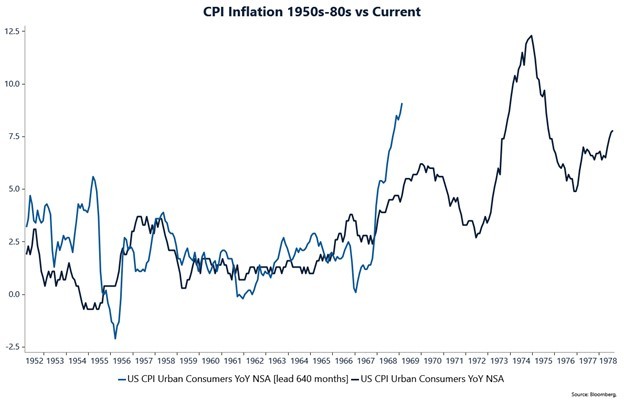

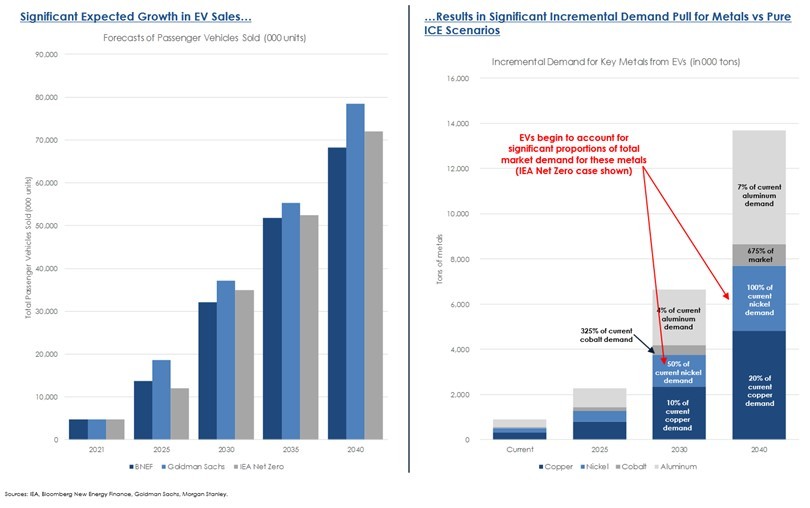

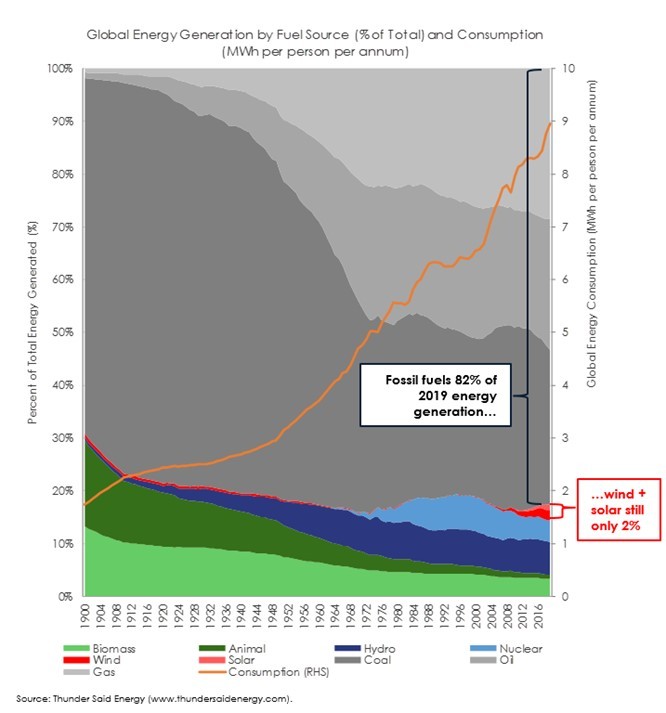

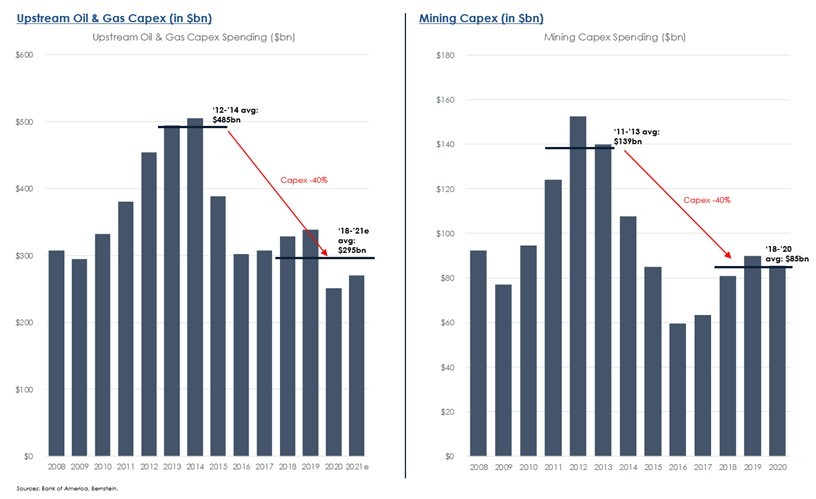

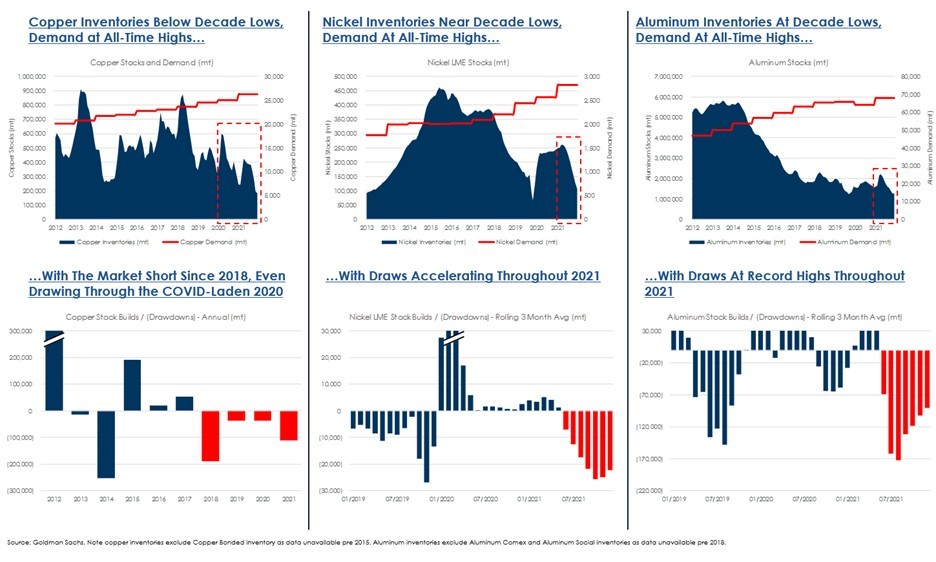

Our own analysis also shows[4] that we do not anticipate the favorable inflation outcomes of the past three decades to continue over the next few decades. Apart from a stronger fiscal position, the favorable inflation environment of the past three decades was partly due to the increased global productive capacity resulting from the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the inclusion of China and India in the global trading market. Additionally, financial markets had become more interconnected, resulting in the greater deployment of the world’s savings toward cross-border investment financing. These factors contributed to lower inflation expectations and reduced risk premiums.

[1] Source: Itamar Drechsler, Alexi Savov, and Philipp Schnabl, “Why do banks invest in MBS?,” New York University Stern School of Business, March 13, 2023.

[2] Modern Macro by Zachary Cameron.

[3] Lubik, Thomas A. (September 2022) “Analyzing Fiscal Policy Matters More Than Ever: The Fiscal Theory of the Price Level and Inflation” Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Brief, No. 22-39.

[4] Macro Minute: What If (Dec 2022), Macro Minute: A Tale of Two FOMCs (Nov 2022), Catalysts Into Year-End (Oct 2022), Macro Minute: We Learn From History that We Do Not Learn From History (July 2022), Norbury Partners 2022 Annual Report (June 2022), Macro Minute: Flat as a Pancake (Mar 2022), Macro Minute: The Reflexivity of Inflation & Conflict (Mar 2022), Macro Minute: Speak Harshly and Carry a Small Stick (Feb 2022), Special Report: A Changing Paradigm (Aug 2021) – for any of these reports, please contact [email protected] or visit our website.