Despite all the efforts of the most brilliant economists and analysts in the world to build models mimicking the methods of physics that follow their own self-contained logic, rules, and patterns to predict outcomes, when faced with failure, they dismiss it by claiming that “random shocks” had somehow disturbed equations and did not need to be explained since they are “nonrecurring aberrations.” War, pandemics, and politics are not abnormal historical events, only in economics.

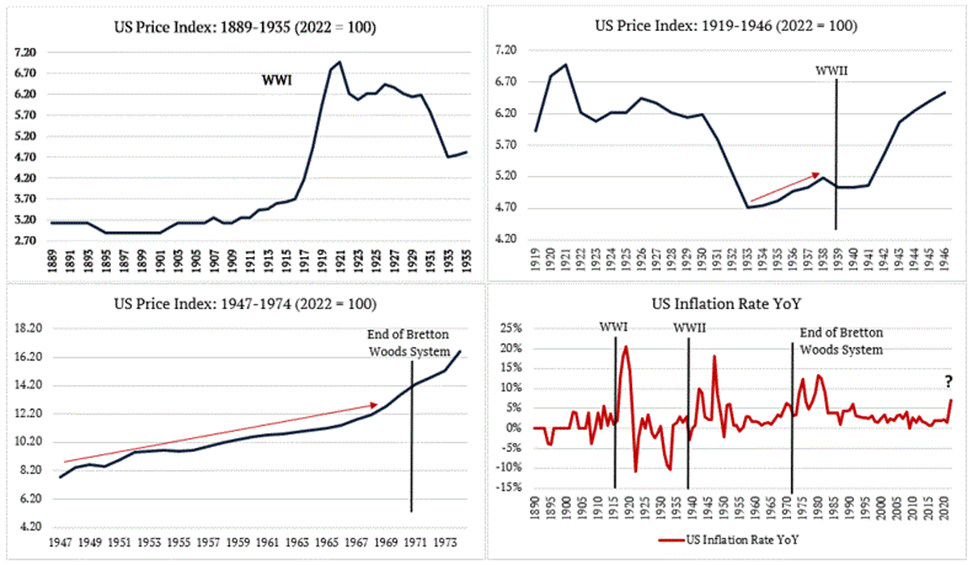

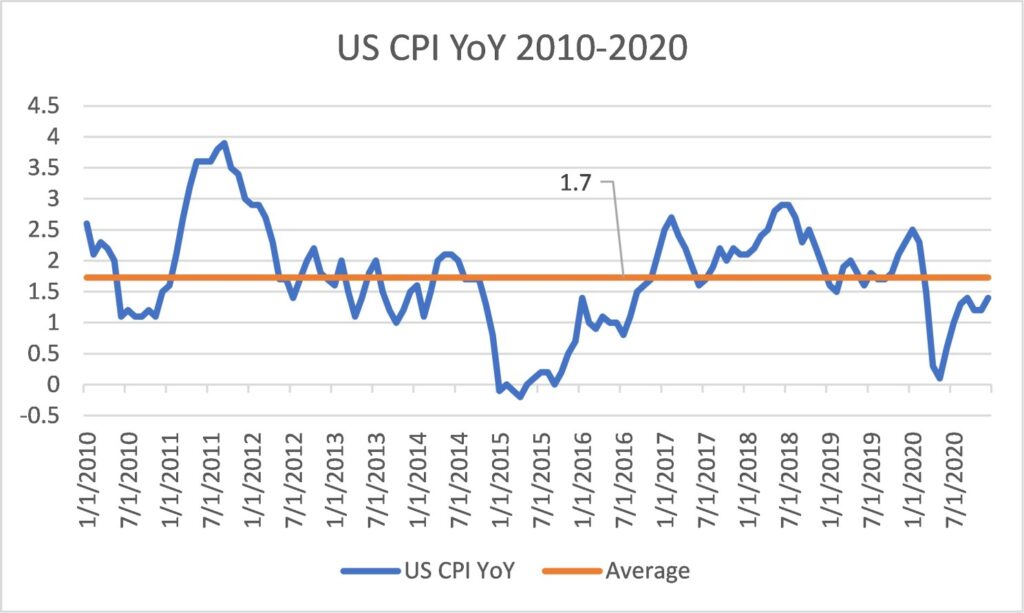

However, many questions in economics can be approached more simply through history. In the most recent record, from 2010 to 2020, US CPI YoY averaged only 1.7%, below the Fed’s target (how much did that play a role in the recent late response from the Central Bank is anyone’s guess). However, in the history of the US, there are only a handful of times that the inflation picture could be described as stable.

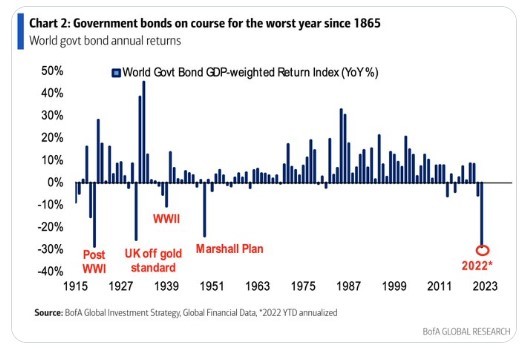

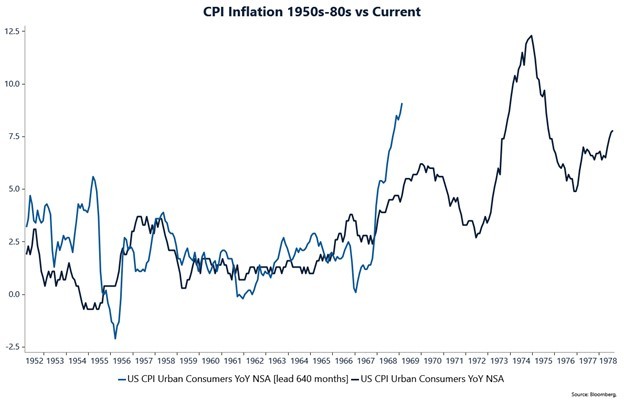

Looking back at American history, we find six inflationary spiral events. The first occurred in the late 1700s just after the Revolutionary War; the second in 1813 after the War of 1812; the third in the 1860s during the Civil War; the fourth in the late 1910s after World War I; the fifth around and after World War II in the mid-1940s; and, the most current one in the 1970s associated with the Vietnam War. These periods were always followed by long periods of deflation. Evidence would point to politics, not economics, to explain inflationary spirals, and war looks like the common denominator. War in itself has many different impacts on inflation (as we discussed in this Macro Minute: The Reflexivity of Inflation and Conflict). Still, it is really the increase in money spent by the government, above what it collects in taxes, that makes inflation and negative real rates an attractive solution to the debt problem.

Looking back to the latest inflationary cycles of the 1970s, we find a few similarities and one significant difference. [1]

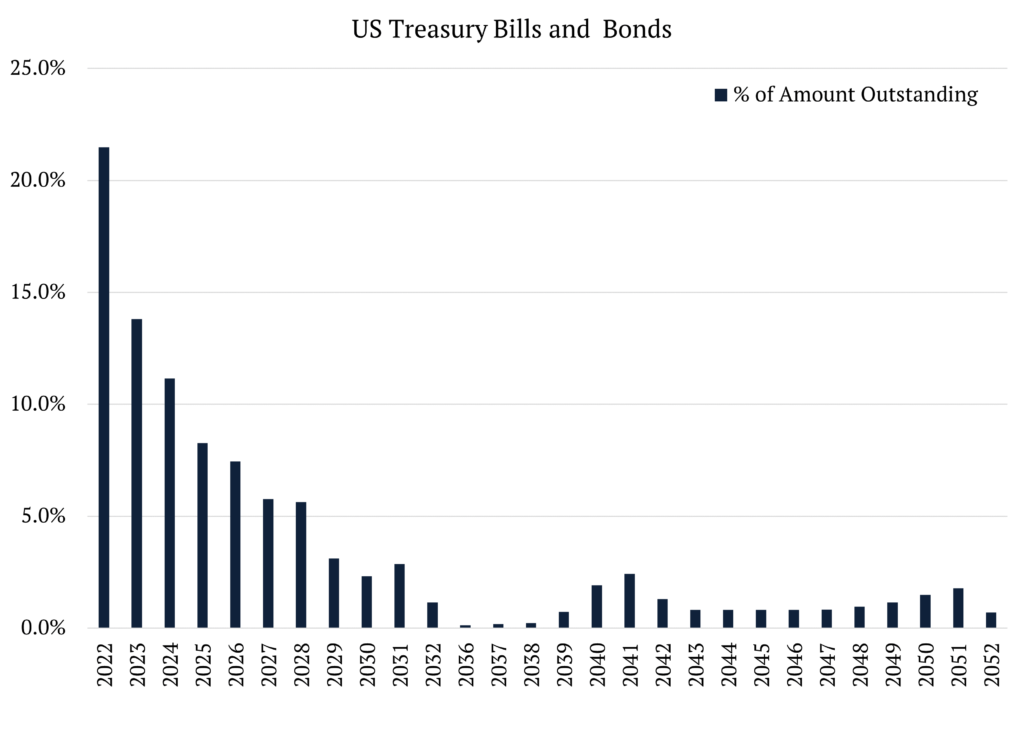

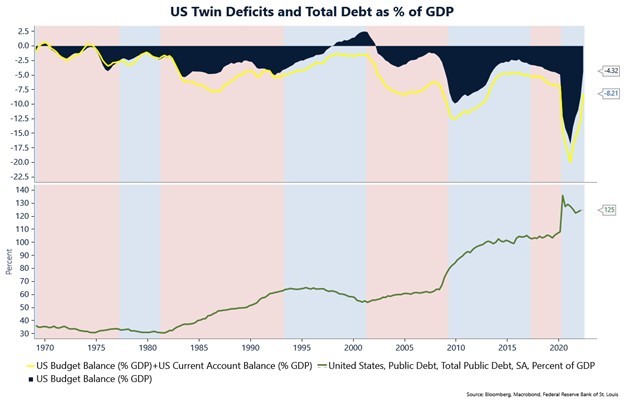

Similar to the present day, in 1975, the government balance sheet resembled conditions only tolerated during periods of war. And in the preceding years, just like recently, conservative governments that were supposed to be fiscally conservative were actually accelerating the deficit. In today’s world, for example, if interest rates rise above inflation, the Treasury’s interest expense goes up as debt rolls over, and the Fed reduces remittances to the Treasury. The Congressional Budget Office calculates that a 1% increase in real rates increases the annual deficit by $250 billion, about 1% of GDP, planting the seeds for an explosive debt dynamic.

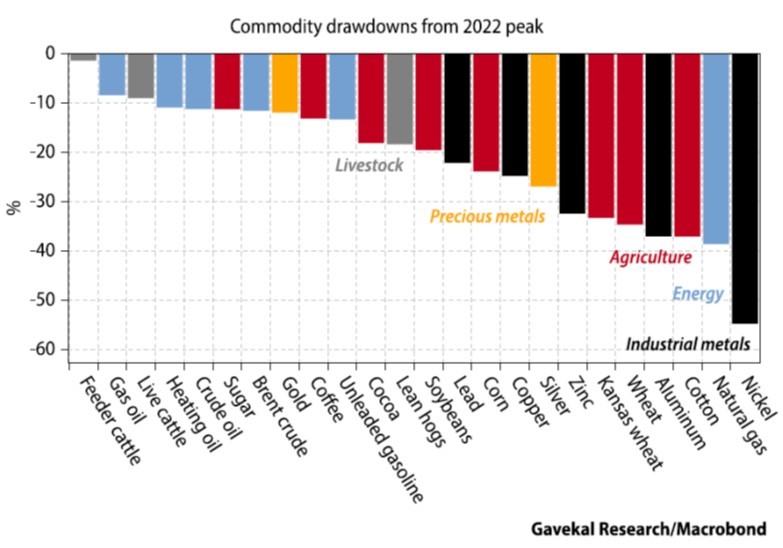

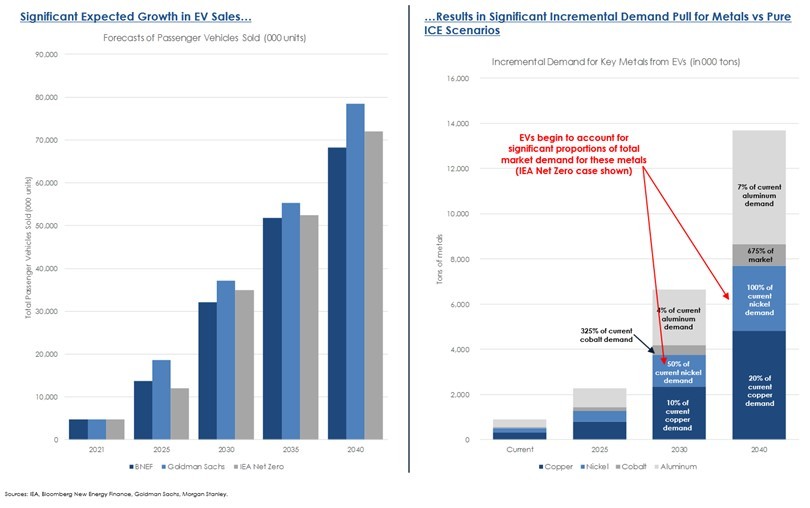

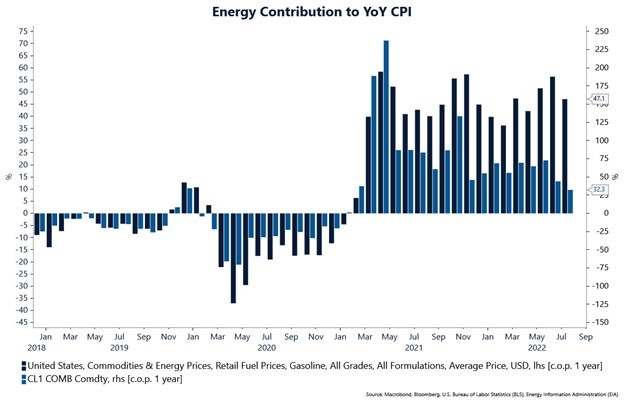

In the 1970s, oil price inflation was a big problem, increasing to around 6 percent per month. More recently, on average, oil has been growing at 4.2 percent per month since January 2021. That includes the price corrections we saw in the last couple of months. The contribution to the CPI is still high at 47% YoY at current gasoline prices.

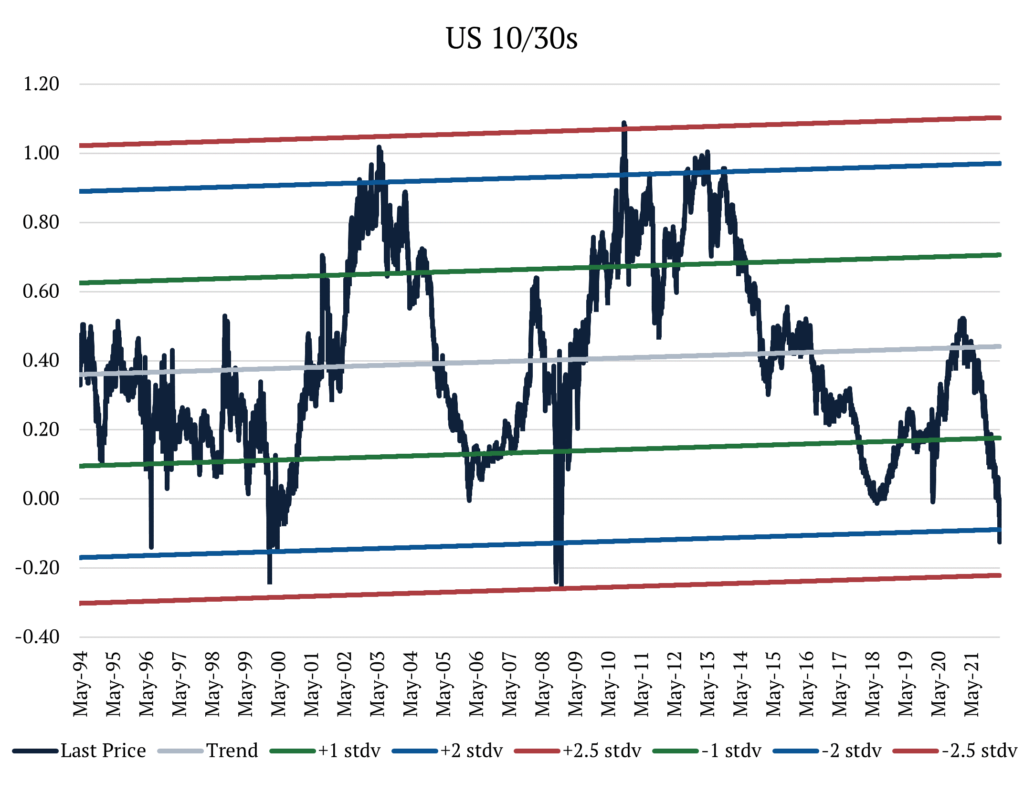

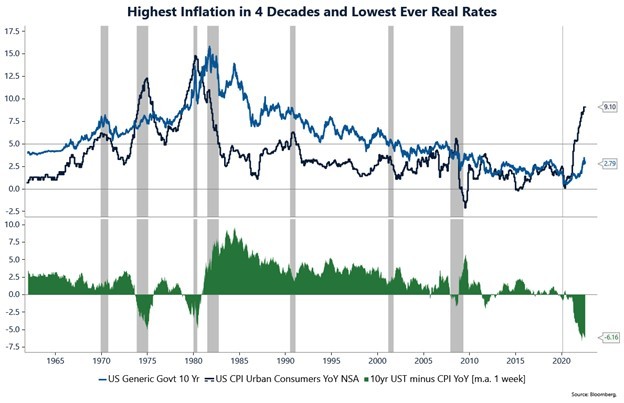

In the 1970s, real interest rates reached -4 percent. Today, we are living through the most extended period of negative real rates, currently sitting at -6 percent. That is before factoring in what can happen with nominal rates in a recessionary scare. We calculate real rates by subtracting the US Treasury 10-year yield by the current CPI YoY number. We believe this is a better indicator of real rates on Main Street than the real rates derived from the TIPS markets on Wall Street. This is the rate that alters the lives and actions of people who are not traders or advisors and who do not follow the FOMC decisions or read the Wall Street Journal. Different from the previous cycle, when the Fed was focused on impacting asset prices, to have an impact on goods and services prices, the central bank needs to focus on the decisions in the real economy and not in financial markets.

“At 15 percent inflation, an investor lending $1 million at 10 percent ‘loses’ $50,000 a year. You cannot count on the lender being a complete idiot, sooner or later, he will stop lending at low-interest rates and invest the money himself in commodities or real estate.” – Senator William Proxmire. October 1979

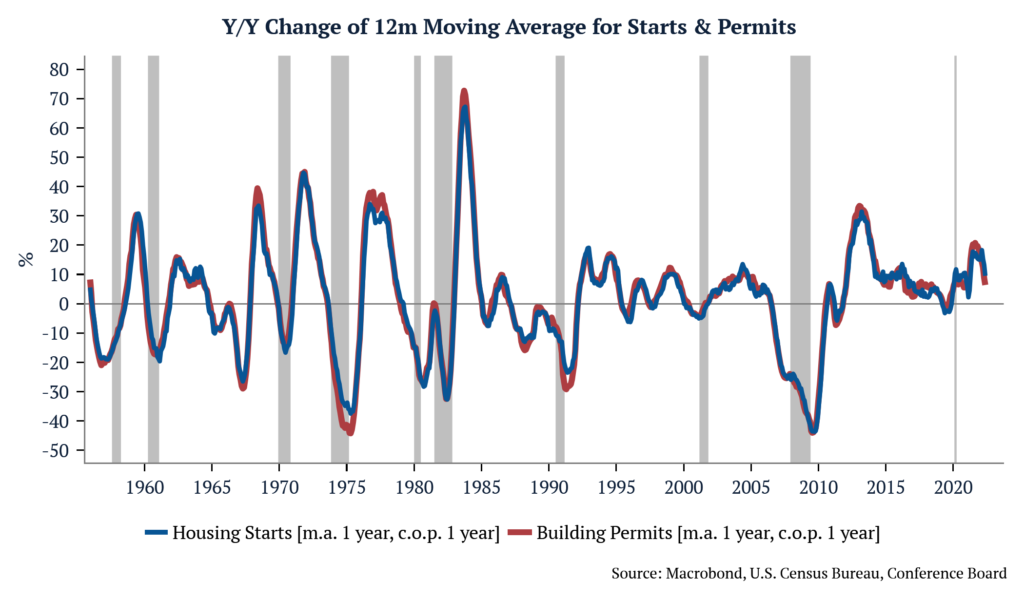

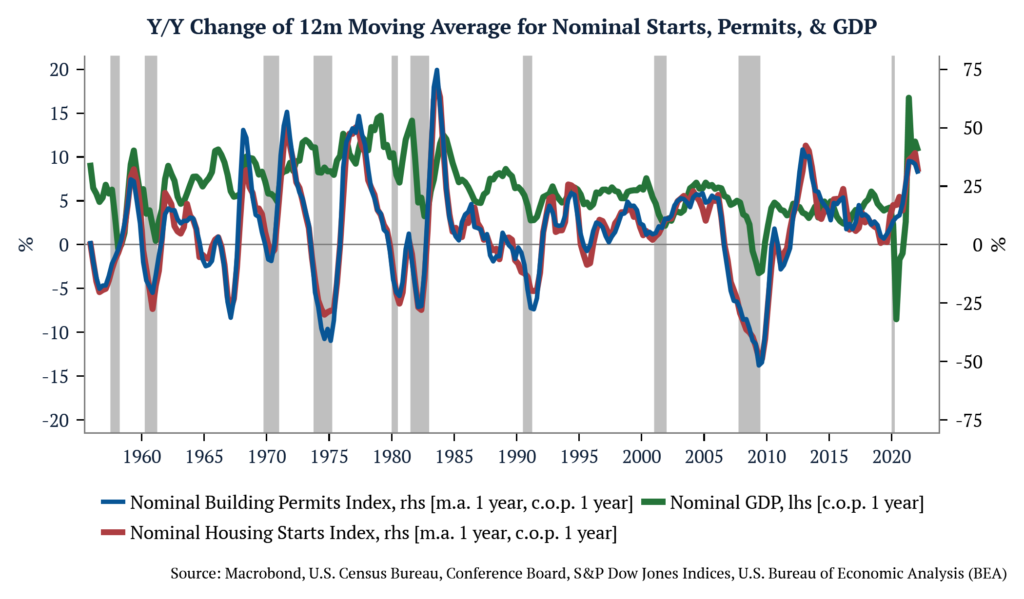

Another interesting observation from looking at real interest rates is that every recession is proceeded by positive real rates. More importantly, real rates tend to turn negative to help the economy once a downturn starts. This brings us to the recessionary debate. Like today, in 1979, most economists, including the Fed, were forecasting a recession. They had been wrong for many months, and in September, data showed the economy was not tipping over; it was accelerating again. This was true even with a deceleration in housing and autos and the fear of recession. “A Gallup survey found that 62 percent of the public expected a recession sometime in 1979.”

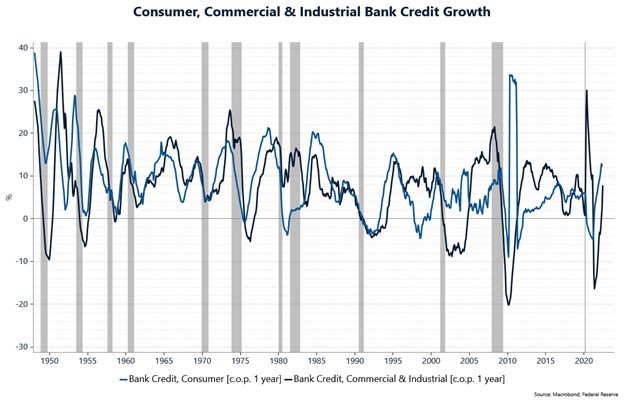

In an inflationary economy, people behave differently. Inflation doesn’t slow people down. With inflation at 16 percent, borrowing at lower rates seemed like a good deal. Bank credit was expanding at an annual rate of 20 percent. Most consumers did not care about what the higher interest rates were, as long as the monthly payments could fit their incomes. This is not a foreign concept for Latin Americans.

“Lenders were still surprised at how many families were willing to take on home mortgages at 13 percent or even higher. ‘ Perhaps it is not so hard to understand,’ Volcker said, ‘when you realize that the prices of houses have been going up at 15 percent or more.’” – 1979

Today, bank credit is growing at +12% for consumers and +8% for Commercial and Industrial clients. We’ve been following bank’s earnings calls very closely and we find that all the major banks see strong balance sheets, very low forward-looking default rates, and expect credit to grow in the mid-teens for the next few quarters. This past week, American Express reported that overall cardholder spending rose 30% from a year earlier.

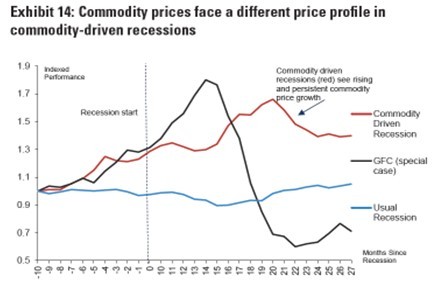

Even when the Fed was finally able to create the presumed remedy, a prolonged recession that endured for 15 months with unemployment rising to 9.1 percent and industrial production shrinking to roughly 15 percent, as soon as the economy recovered, inflation came roaring back, rising even higher than before even with employment never getting close to its natural rate. With the supply of commodities constrained, even a short-term decrease in demand does not fix the inflation problem; it only postpones it to the following part of the cycle when policies revert to accommodative.

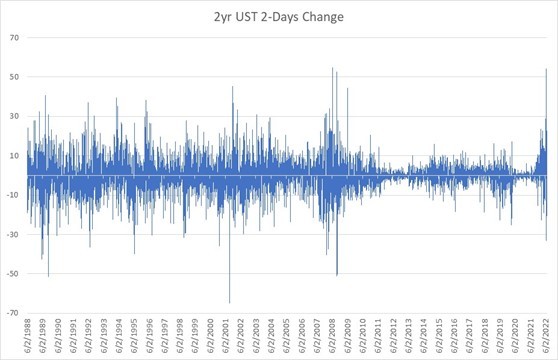

Lastly, the Fed genuinely did not know how much interest rates would have to rise to break inflation. If record levels of rates were not fixing the problem, how high would rates need to go to do it? Nor did it have the political capital to do what was necessary. Volcker acknowledges, ‘We could have just tightened, but I probably would have had trouble getting policy as much tighter as it needed to be. I could have lived with a more orthodox tightening, but I saw some value in just changing the parameters of the way we did things. (…) it would serve as a veil that cloaked the tough decisions.’”

“There is a wide concern about the Fed’s resolve in adhering to this policy in the face of an election year and the increasing likelihood of a recession. If strong words and actions are not followed by results, then holders of dollar-denominated financial assets in the US and abroad will conclude that the recent changes are no more significant than the statements and policy changes of prior years which did not reduce inflation. When rhetoric sufficed several years ago, tangible proof is now required of the Fed’s intentions.” – Federal Advisory Council 1979

The similarities are striking.

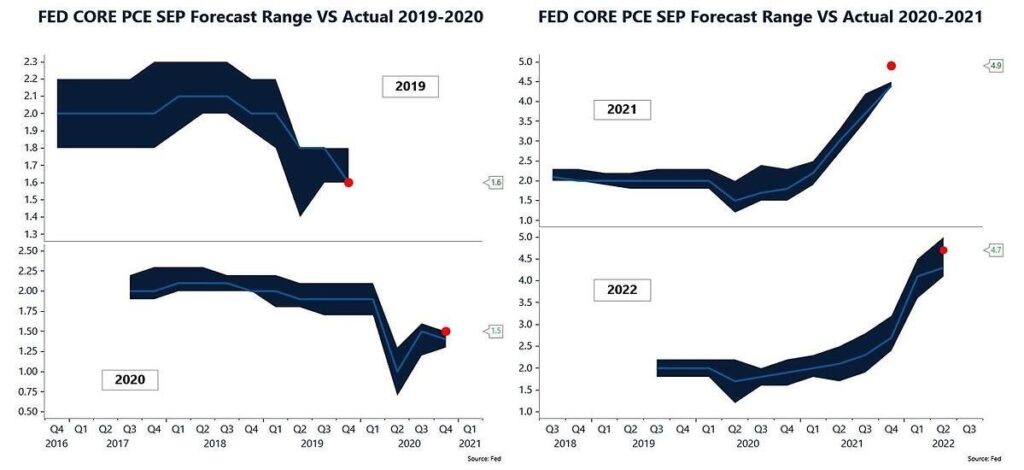

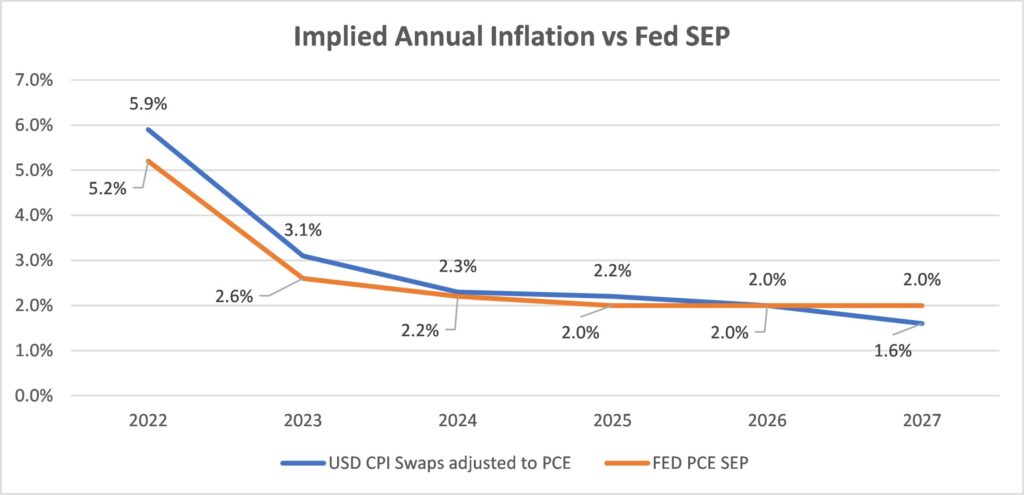

The main difference between the 1970s and today lies in the credibility that central banks around the world collected during a period of global deflationary forces that made them look like they could bend prices to their will and achieve their dual objective effortlessly, giving rise to the mantra “Don’t fight the Fed!” On July 14th, 2022, Governor Waller said, “The response of financial markets to the FOMC’s policy actions and communications indicate to me that the Committee retains the credibility and the public confidence that is needed to make monetary policy effective. (….) lenders and borrowers are still doing business at these rates, which indicates that they believe the FOMC’s policy intentions are credible, as broadly reflected in the interest rate paths in the Summary of Economic Projections (SEP).” Today, markets price the Fed’s projections to perfection.

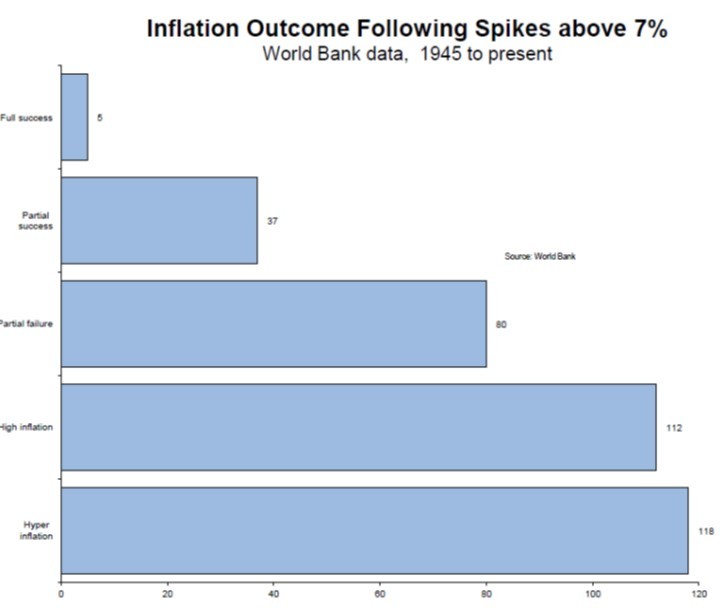

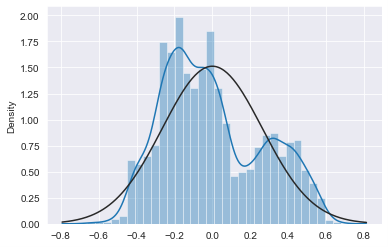

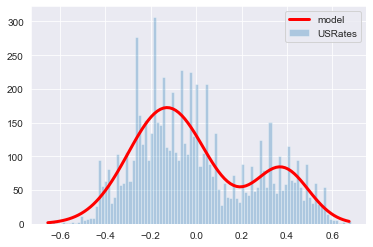

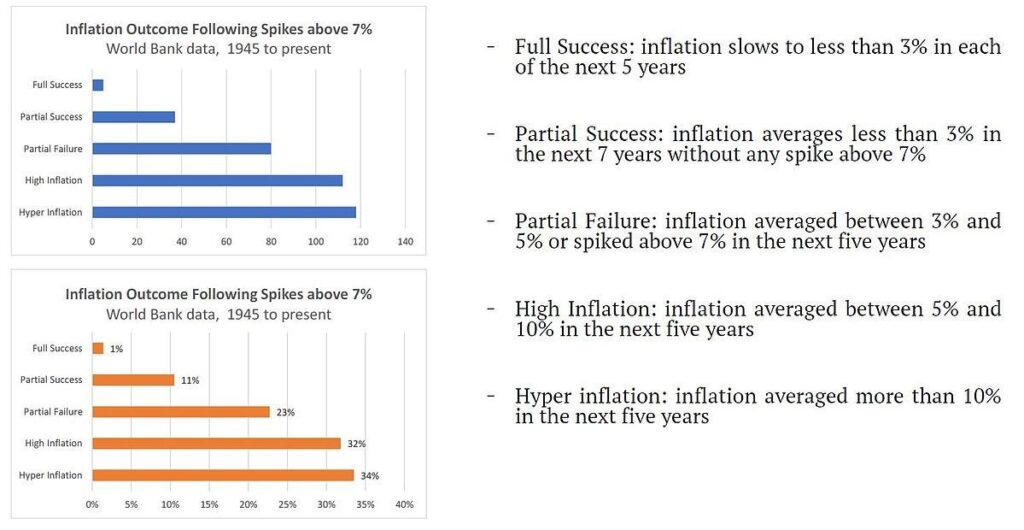

What does history tell us about that? StoneX’s Vincent Deluard shows us that using post-war data from the World Bank of more than 350 events when inflation spiked above 7%, only 1.4% of the time, inflation slows to less than 3% in each of the next five years. Markets are pricing 1 in 70 odds as if it were 100 percent certain.

“Acting hastily is essential to [a trader’s] profitability. If today’s quickest-to-the-keyboard move makes little sense according to some notion of ‘fundamentals,’ who cares? Overshooting is a feature, not a bug.” – Alan S. Blinder, July 2022.

“Traders must and do therefore respond literally instantly to all news to which they think other traders might respond. Whether the news is considered economically significant or even true is immaterial.” – Albert Wojnilower, Chief Economist at First Boston 1964-1986

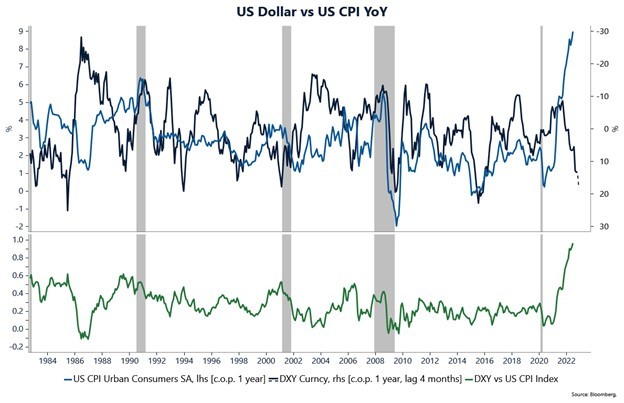

This confidence also has an impact on the USD. With the expectation that inflation will converge to 2% in the next 18 months, interest rate differentials make the currency attractive. That, in turn, keeps inflation in the US in check. The DXY Dollar index is more than 17 percent up YoY, while the US CPI is 9.1 percent. Being conservative, we can assume a short-run currency passthrough in the US at about 25 percent.[2] This means that if the US Dollar was flat year-over-year, inflation should be a whopping +13%! This blind faith in central banks is what is keeping everything together. But history also tells us that after a long deflationary cycle and the build-up in credibility, what comes next is the drawing down of goodwill until there is nothing left.

“We’ve lost that euphoria that we had fifteen years ago, that we knew all the answers to managing the economy.” – Volcker 1989

[1] A good friend of the firm and fellow investor, knowing of our quest to understand history, pointed out to us that the team at MacroStrategy research was studying a book written in 1989 by William Greider called “The Secrets of the Temple” about the Fed’s fight against inflation under Volcker to help them with a similar pursuit. This book has been invaluable in our understanding of the period, and all quotes in this letter are from the book. https://www.amazon.com/Secrets-Temple-Federal-Reserve-Country/dp/0671675567/

[2] Campa, Jose Manuel, and Linda S. Goldberg. “Exchange rate pass-through into import prices.” Review of Economics and Statistics 87.4 (2005): 679-690. (https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w8934/w8934.pdf)

Exchange Rate Pass-Through and Monetary Policy, Governor Frederic S. Mishkin, at the Norges Bank Conference on Monetary Policy, Oslo, Norway. March 07, 2008 (https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/mishkin20080307a.htm)

Takhtamanova, Yelena F. “Understanding changes in exchange rate pass-through.” Journal of Macroeconomics 32.4 (2010): 1118-1130. (https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/wp08-13bk.pdf)