If you haven’t had the opportunity to read Part 1 from this series of Special Reports on the United States election, you can find it here. As a refresher, we used a combination of historical and mathematical analysis to arrive at probabilities for a Biden-Harris win and a Blue Wave, defined as a Democrat-controlled House, Senate, and Oval Office. Below, we will begin with a quick update of our election forecasts before moving onto the prospective impact of said forecasts on fiscal policy. We will then more closely examine the high-level and near-term spending implications of former Vice President Biden’s policy agenda on industries and sectors before wrapping up with a look at how a bipartisan push for antitrust legislation might manifest.

Refreshing Probabilities: Senate Seats Matter

With two weeks left until Election Day, our current forecasts estimate a 91% chance of Mr. Biden winning the presidency and a 69.3% probability of a Blue Wave. Our Blue Wave probability includes all permutations of contested Senate races that would result in a 50-50 split or better for Democrats (given the Vice President holds the tiebreaking vote in the Senate). The probability of Democrats having at least 50 seats is 76%, which drops to 44% for 51 seats, 15% for 52, and quickly converges toward zero as we add more Democrats to the Senate. This is an important distinction to make before discussing fiscal policy because a 50- or 51-person majority will require a legislative agenda that satisfies moderate centrists for Democrats to carry the necessary votes. For this reason, we continue to closely monitor Senate races in states like Iowa and North Carolina that will ultimately decide the balance of power in the Senate, and thereby guide our views on impending fiscal policy and subsequently, our market outlook.

Under current rules, Congress can make changes to taxes and benefits programs with a simple 51-vote majority in the Senate through use of the budget reconciliation process. However, annual spending bills (appropriations) and the establishment of new programs require a filibuster-proof 60 votes to pass the Senate, as do changes to regulatory policy, antitrust law, immigration, and minimum wage. Elimination of the filibuster has been floated by both parties since the turn of the century and will be under consideration in the case of a marginal Blue Wave in order to expedite the passage of Democratic legislation, but is unlikely to be the first bill passed.

Although it would require bipartisan support to reach 60 votes, we view the passage of an infrastructure bill in the second half of next year after another virus relief package as the most probable leg of Blue Wave fiscal policy. Subsequently, we view a broad reconciliation bill covering changes to healthcare and tax increases as likely to follow, needing only 51 votes, but with a lower probability considering the support needed from moderate Democrats in a 50- or 51-Democrat Senate. The last and least probable pillar of Mr. Biden’s legislative agenda is education, which would need to pass with 60 votes and extends from pre-K to university, drawing on former candidate Senator Bernie Sanders’ bill for higher education.

Fiscal Policy for a Blue Wave

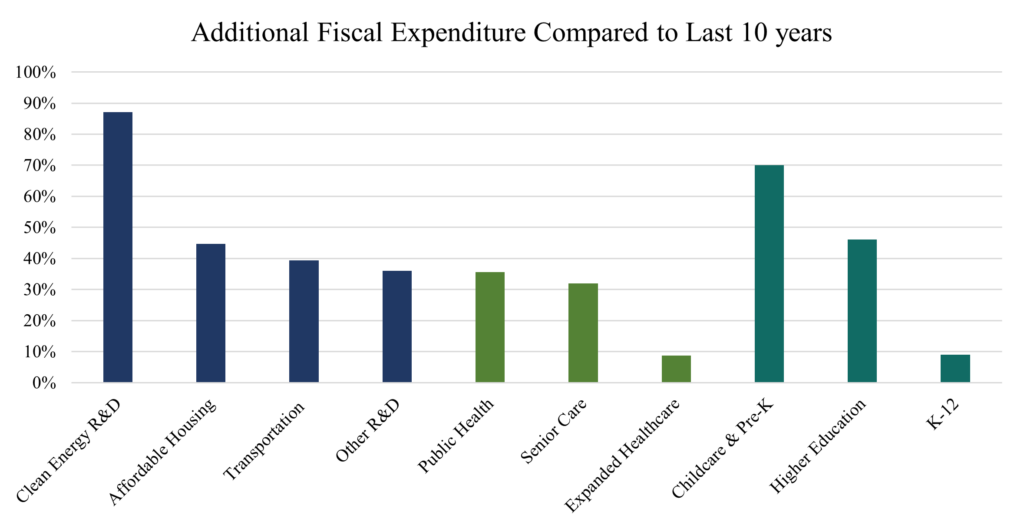

Notwithstanding a Covid-19 stimulus package, the Biden-Harris ticket has set forth an aggressive fiscal agenda with estimate gross spending between $9-10 trillion over the next ten years. They intend to offset approximately $5 trillion of this spending through tax increases, budget reappropriations and savings. Our analysis here is focused on gross additional spending over the next decade, how it compares to spending this past decade, and how much of the spending we estimate to occur during Mr. Biden’s first term.

We’ll begin with an examination of spending on infrastructure, research, and development. It is interesting to note that private investment in fixed assets (specifically residential and non-residential buildings, industrial equipment, and transportation equipment) was just over six times that of government investment in infrastructure (mostly transportation) from 2010 to 2019 – in other words, every $1 committed to government infrastructure investment resulted in $6 of investment from the private sector. At this point, it remains unclear if Democrats’ infrastructure and R&D policies will crowd out the private sector, or if they will be additive and result in private sector expansion. Former Vice President Biden’s Build Back Better infrastructure plan contains $2 trillion in funds earmarked mainly for transportation and clean energy infrastructure, but also includes $300 billion for research & development, $300 billion for housing construction, and $100 billion for education-related construction. In aggregate, the Congressional Budget Office estimates the net increase in infrastructure spending will amount closer to $450 billion over 10 years, but expect a Democratic Congress to at the very least pass legislation that boosts infrastructure spending by a few hundred billion over the next 5 years, including tax incentives for renewable energy.

Government investment in non-defense energy, natural resources, environment, and general science research and development totaled $172.6 billion from 2010 to 2020 – this plan pledges an additional $150 billion, or an 87% increase over the next decade, to clean energy research and development. Mr. Biden’ plan also commits $750 billion to affordable housing through expansion of Section 8 and a tax-credit for first-time homebuyers. Last year’s data shows that 33% of homes were purchased by first-time buyers and 4% of United States households are on some type of federal housing assistance. Using this as an approximate basis for private sector spending in these areas, this amounts to a 44.7% increase in spending on first-time homeownership and affordable housing over last decade. Assuming half of the $2 trillion is invested in transportation projects over the next ten years, Mr. Biden’s plan will have committed an additional 39.4% of total investment by state, local, and federal governments this decade. Finally, he has pledged another $150 billion to healthcare, infrastructure, and telecom research and development, which amounts to about 36% of healthcare and transportation R&D in the past decade. Research spending is the most frontloaded of his agenda, with approximately 30% expected to occur within his first term.

Moving on to healthcare, where total spending in the next decade is expected to be approximately $2.8 trillion, not including expanded social security or supplemental security income. Mr. Biden’s healthcare plan includes $300 billion for rural health, mental health, and to aid the opioid crisis. In practice, this means doubling federal funding for Community Health Centers, increasing payments to rural facilities, and expanded funding for mental health services. When compared to aggregate spend on public health activity since 2010, this sums to a 35.5% increase for the next decade. Support for the elderly and those in need of long-term care is expected to increase by $600 billion, an estimated 32% of total public and private spending on senior and elderly living care from 2010 to 2020. The final leg of his plan intends to build on former President Obama’s Affordable Care Act by expanding subsidies and enrolling low-income families in premium-free coverage. The estimate cost of expanded health insurance coverage for Americans is $1.9 trillion, which is only 8.7% of the staggering $21.9 trillion that has been spent on private health insurance, Medicare, and Medicaid in America since 2010. Altogether only about 21% of this spending is expected to occur during the Biden-Harris first term.

Ending with education, where our estimates show aggregate spending in excess of $2.5 trillion over the next decade. Mr. Biden’s plan includes access to free pre-K for all children aged 3-4 through a mixed delivery system combining public schools and private care centers. Additionally, he plans to make the existing tax credit for child and dependent care fully refundable and expand it to cover half of all expenses for one or more children, capped at $8,000 and $16,000 respectively. Biden’s agenda for the Childcare Support & pre-K program is $325 billion over the next decade – which would add 70% to aggregate investment in childcare and pre-K as compared to the previous decade. The largest of the educational spending programs is for higher education, where estimated spending, including free tuition to public universities and colleges for families below $125,000 in income, is $1.6 trillion. This amount of stimulus is equal to 46% of total expenditures by public higher education institutions since 2010 and will grow given the desire to legislate future forgiveness of student loans. In other words, a Blue Wave would result in the federal government covering nearly half of all tuition paid at public higher education institutions in the past decade! Conversely, the additional funding apportioned to support K-12 education in inner cities and for disabled students is a big headline number, $600 billion, but would only represent an increase of about 9% of total public school spending compared to the last 10 years. In total, about 28% of this spending is expected to occur in Mr. Biden’s first term using a 2022 start-date for the education stimulus due to legislative timing.

Former Vice President Biden has laid out an extensive fiscal policy agenda that will be most affected by the Senate results November. We have looked closely at his policies and identified a few key sectors to follow as we begin to position for a Blue Wave: clean energy, homebuilders, industrials, and healthcare.

Implications of Bipartisanship on Anti-Trust

In addition to aggressive fiscal policy, a Democratic White House and Congress might seek substantial changes to antitrust law and, in the process, re-order the mergers and acquisition market for a very long time.

Even with markets slowed by Covid-19, North American M&A activity reached $226.8 billion over 2,205 transactions in Q2 2020 alone. The United States has developed a robust and well understood body of antitrust law to regulate the M&A market and prevent, or at least impede, anticompetitive market concentration of power and the rise of monopolies. This issue has gotten very real attention from the House of Representatives in connection with their investigation concerning whether giant US tech companies have acquired and exercised anticompetitive power in digital and online marketplaces. On October 6, the House Judiciary Committee concluded a 16-month investigation asserting that these large tech companies have very much done so and that there is a “clear and compelling need to strengthen antitrust enforcement.”

The report carries with it the potential, if the recommendations are adopted, to restructure the M&A marketplace as it flips presumptions that have been in place in antitrust law since Standard Oil was broken up as a monopoly in 1911 after the U.S. Government sued it for violations of the Sherman Act. The presumption, under the report, is that companies wishing to merge will have to prove that their mergers or acquisitions are not anticompetitive instead of it being the responsibility of the Government to prove that the mergers or acquisitions are anticompetitive; this is a significant shift. A consequence from this is that we may see many more creative and innovative forms intended to defeat or impede government review – for example, joint ventures where there is no formal combination but in which form the result could still be the same – concentration of market power but now without formal antitrust review.

The Committee also proposes to block all acquisitions of potential rivals and nascent competitors. It suggests that such activity be considered presumptively anticompetitive and thus prohibited. This might have the unanticipated consequence of, in the tech space, deterring startups and innovation as founders lose a natural exit. In the pharmaceutical space, where much of the R&D for truly innovative products is outsourced to startups who are then later acquired, this could have the effect of depriving the world of significant medical treatment research and advancement as drug companies can no longer buy potential competitive bio-tech research firms with interesting advances.

All things considered, the report is a clarion call to Congress to take a leadership role in antitrust policy formulation and enforcement. This would represent a major change in the entire market as professionals who have previously guided antitrust policy and enforcement are replaced by those who are instead governed by a two-year fundraising and election cycle. This is coupled with a significant call to re-invigorate private antitrust enforcement by undoing or eliminating significant amounts of precedent and jurisprudence related to antitrust actions, including lowering the standards by which a court should even evaluate a pleading. This will, if taken up, result in a massive amount of private litigation risk that every merger or acquisition will now have to expect and plan for. It remains to be seen whether the current M&A insurance market or the policies that insurance companies have written for directors and officers will cover the private litigation risks that might be a natural consequence of some of the changes presented in the face of a Blue Wave.

Currently, antitrust law has bipartisan support, and as laid out by the House committee, presents meaningful future risks to the technology sector and could result in systemic market disruption after the election. We are closely following both parties’ rhetoric and the evolution of the House Committee and Supreme Court’s views into and past Election Day as we measure current and future US market risk.

As always, we will continue to monitor markets, polls, and macro data to update our views. We appreciate you taking the time to read part 2 of our series on US Elections. If you have any questions, please don’t hesitate to get in touch with one of us.

Sincerely,

The Norbury Partners Team