For many decades now, world leaders have slowly come to terms with the realities of climate change. More recently, we have seen the public and private sectors starting to translate promises into actions through various investments. As we move from theory to practice, agents are beginning to run against obstacles that were not clear before.

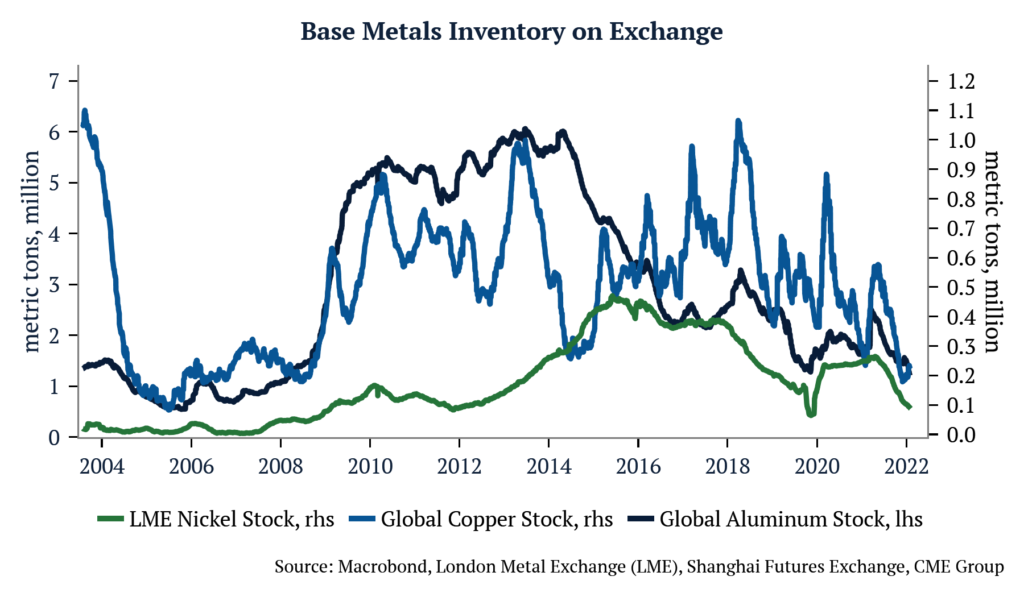

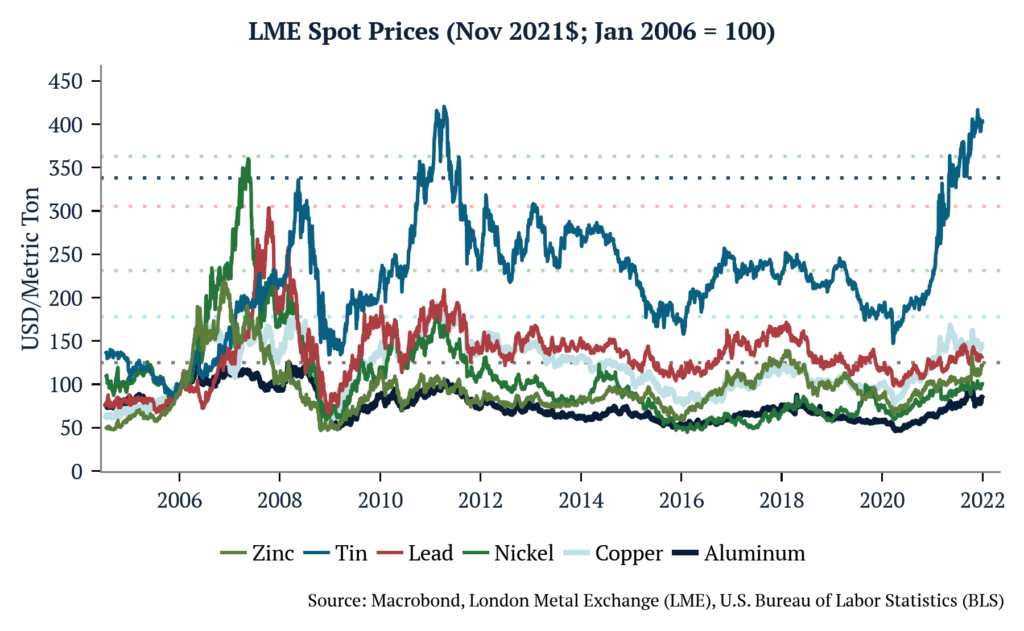

It has become increasingly clear that the world lacks the investment in natural resources necessary to make the green energy transition a reality. Setting aside the requirements for building solar and wind power on a global scale, the Geological Survey of Finland (GTK) recently released a study examining the volume of metals needed to build the first generation of electric vehicles (e.g., replacing every vehicle in the global fleet today with one EV) and the power stations (e.g., batteries) necessary to store intermittent electricity generated from renewable sources. They estimate that one generation of electric vehicles (1.39 billion) will require over 280 million tons of minerals and another 2.5 billion tons of metals for power storage projects to support such an increase in electricity consumption. In sum, current estimates for global reserves of nickel, cobalt, lithium and graphite are not sufficient to support such a massive undertaking.

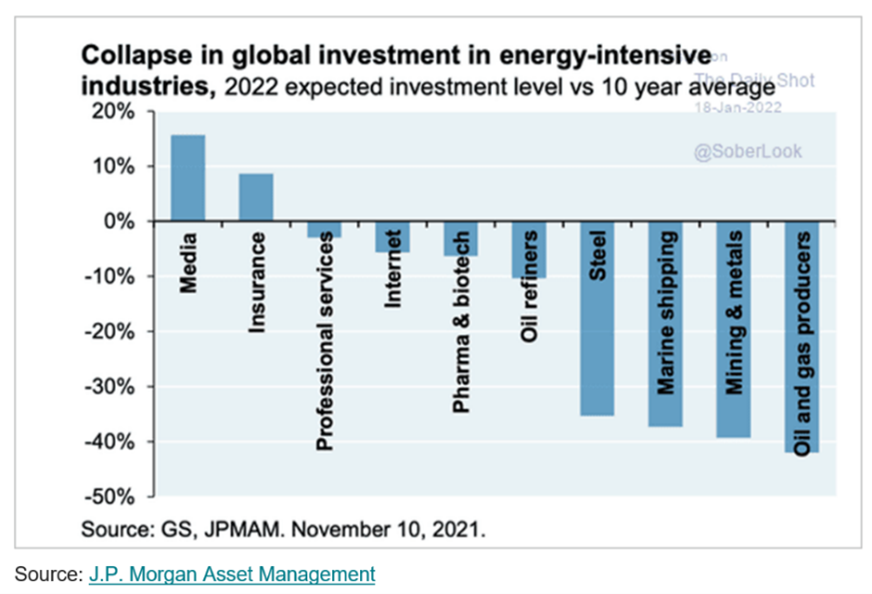

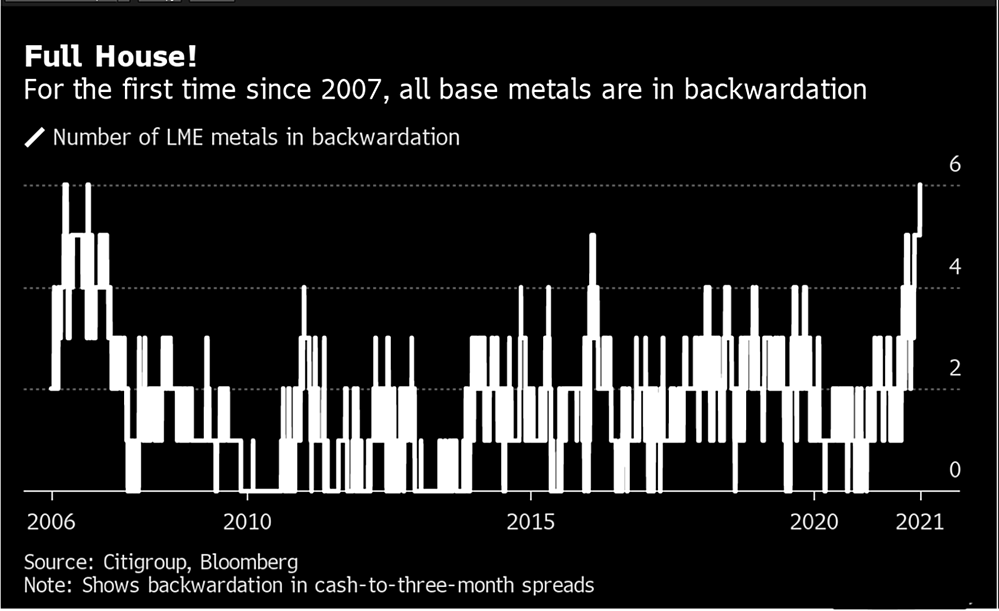

To aggravate the problem, investments to transform reserves into actual ore are faltering. Existing mines for copper in places like Chile have under-produced expectations meaningfully this year. Reports from the recent 121 Mining Conference in Sydney highlighted the issues of getting new projects approved and on track for production, characterizing the challenges as “multiplying” for myriad reasons, including higher interest rates, low and volatile mineral prices, and ESG concerns.

On the geopolitical front, the ongoing realignment of world power will also have a material impact on access to materials and their ESG qualities. The world’s largest nickel producer is Indonesia, where mines are developed in the most biodiverse biome on the planet—rainforests; its biggest and cheapest nickel operation is Nornickel, located in Russia. The world’s largest cobalt producer by far is the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), where not only does the climate range from tropical rainforest to savannahs, but also the exploitation of child labor is a major social concern. While China is responsible for 64% of graphite mining, it also has a controlling interest in much of the DRC’s cobalt production, and maintains an overwhelming majority of the refining capacity for lithium, nickel sulfate, manganese and graphite.

The unprecedented demand for green-transition minerals meets a supply picture that is very constrained and will generate prohibitive costs to the energy transition. That happens while billions of people lack cost-effective access to the energy they need to prosper.

Deep-sea mining offers a very interesting alternative to this problem. The USGS estimates that the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, “the largest in area and tonnage of the known global nodule fields,” contains 21.1 billion tons of dry nodules. Based on that estimate, tonnages of many critical metals in the CCZ nodules are greater than those found in global terrestrial reserves. Given the high ore grades found in nodules, and the simplicity of recovery, many companies in the space estimate that deep-sea nodule recovery will be one of the lowest cost producers of critical minerals in the world. The same USGS publication mentioned above notes, “if deep-ocean mining follows the evolution of offshore production of petroleum, we can expect that about 35–45 percent of the demand for critical metals will come from deep-ocean mines by 2065.”

Like any extractive activity, this kind of endeavor also carries costs along with its benefits. However, their costs are different from what one would think at first. The vanguard of deep-sea mining does not involve drilling and mining pits. Instead, it is focused on the harvesting of nodules. Nodules are fist-sized lumps of matter that collect on the ocean floor over thousands of years when currents deposit mineral sediments. Different parts of the ocean contain nodules rich in different elements. Those found in the Pacific Ocean have been shown to contain incredibly rich deposits of copper, nickel, cobalt, and manganese with ore grades superior to many, if not all, of today’s land-based reserves. Nodule collection occurs between 4,000-6,500 meters in the aphotic zone where sunlight does not penetrate and biodiversity is faint. Its process is minimally invasive and entails the scraping of about 6 inches of the ocean floor to separate nodules from sediment, depositing most of what is not used back to its original place. MIT researchers recently published results of a study demonstrating that 92% to 98% of the sediment either settled back down or remained within 2 meters of the seafloor as a low-lying cloud. The plume generated in the wake of the collector vehicle stayed roughly in the same area rather than drifting and disrupting life above.

The benefits are potentially many. From an environmental point of view, this process has enormous advantages when it comes to the impact on deforestation, destruction of carbon sinks, and water usage. From a social aspect, deep-sea mining also appears to be superior to other extractive activities on land, with limited exposure to the negative social dynamics of social displacement, corruption and child labor. If proven to be cost-efficient, it would also promote clean and cheap energy creating prosperity for billions of people. Should the environmental studies of nodule collection continue to be positive, nodules present a promising alternative to solve our natural resource problem in the face of a green transition. As the West looks to become both greener and less dependent on “unfriendly” sources of labor and natural resources, it must take a pragmatic approach toward deep-sea mining, recognizing that there is no such thing as a perfect solution, but this could be the next best thing for achieving the future we want.

This article appeared on Forbes.